John Kenny, Dragon Voices: The Giant Celtic Horns of Ancient Europe. Delphian Records (DCD34183), 2015.

John Kenny, Dragon Voices: The Giant Celtic Horns of Ancient Europe. Delphian Records (DCD34183), 2015.

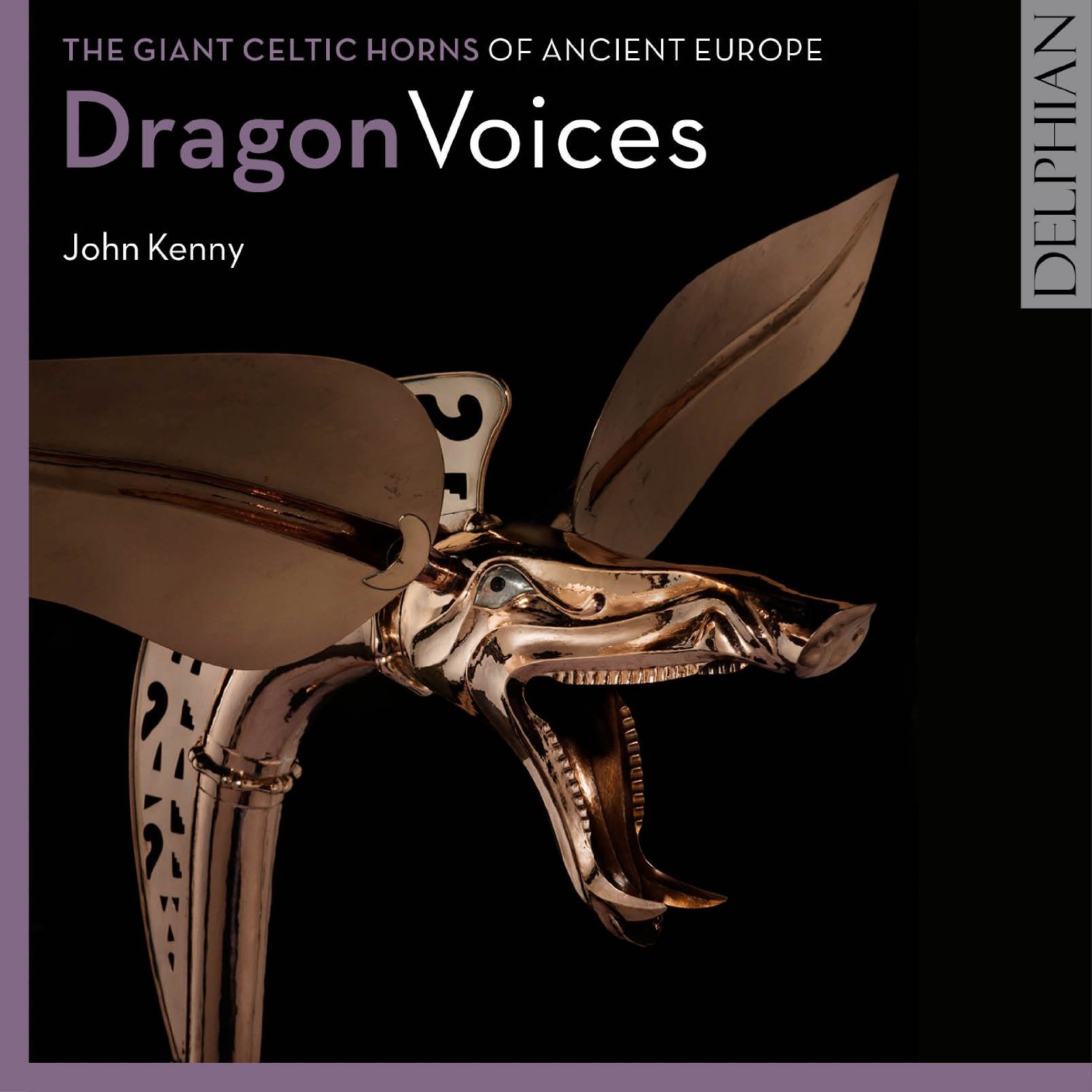

John Kenny; Carnyx, Loughnashade horn, conch shell, bells and drums.

Recorded November 18-20, 2015.

Those attending the Historic Brass Society Session of the EMAP (European Music Archaeology Project) in Viterbo, Italy in 2015 had the rare experience of viewing, listening to, and playing a number of reproductions of ancient brass instruments. This was the result of a five-year project undertaken by EMAP to reproduce and explore the sound world of ancient Roman, Greek, Egyptian, and Celtic cultures. John Kenny was part of that conference and this recording is an offshoot of his long experience playing and composing music for those instruments. In this CD he primarily plays three instruments; the Tintignac carnyx after a first-century BC original found in Tintignac, France (made by Jean Boisserie), the Deskford carnyx after a first-century BC original found in 1816 at Leitchestown, Scotland (made by John Creed), and the Loughnashade horn after a first-century BC original found in 1794 in Co-Armagh, Ireland (made by John Creed).

The recording includes 21 compositions by John Kenny for solo, duo or trio settings. The two and three part works are the result of studio multitracking. These works are improvisational in nature and comprise multiphonics and many other twentieth and twenty-first century techniques. To this listener’s ear, the pieces explore sound effects and tonal manipulation rather than a more conventional compositional devise of development of themes. Playing and writing contemporary music on and for old instruments, in this case, very old instruments is, to me at least, a perfectly acceptable undertaking. Composers and performers are always on the lookout for different tonal textures and at this stage in the early music movement there is a solid tradition of new works on old instruments. The carnyx and Loughnashade horn are lip-vibrated brass instruments but have their own unique sounds. Certainly similar to modern horns, trombones or even trumpets at times, but not quite. They have their own sound.

The liner notes by Kenny in this CD are wonderful, offering a concise history of these ancient instruments as well as a detailed examination of the important work of EMAP. In those notes he makes the case to explore those sound capabilities through the use of contemporary composition. Another argument could also be made that hearing reproductions of these two thousand plus year old instruments in this context prejudices our ears and imaginations as to what those instruments may have sounded like. Kenny makes the point that physiologically we are no different from people who lived two thousand years ago. True enough. He also goes on to point out that cultural context is the only difference as ancient man was not short of imagination. However, it is the cultural context that is the main point. No doubt, John Kenny’s mind is full of a vast array of sounds (Boulez, Cage, John Coltrane and Cecil Taylor etc.). Ancient man, as Kenny points out, was not in short supply of imagination but was completely without the experience of our sound-world. Hence, the ancients would likely not have attempted to make the sounds created here. Perhaps some additional tracks of the performer playing much simpler “excerpts” on the individual instruments would allow us to formulate a less “prejudiced” understanding of the historical use of these wonderful instruments. That philosophical debate aside, we owe both John Kenny and the others in EMAP a debt of gratitude for bringing these ancient beasts (as the dragon-head bells would indicate) back to life.

-- Jeffrey Nussbaum